In September 2011, I was residing in Dachau, Germany after embarking upon a yearlong volunteer service with Action Reconciliation Service for Peace at the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site. Over the next twelve months, I gave tours to young German school groups, helped students write biographies of former inmates, and promoted several traveling exhibitions. On a crisp autumn day early in my volunteer service, I set out on bicycle through Dachau’s beautiful countryside to explore my temporary home.

For anyone familiar with Dachau’s history, the suggestion that the city’s surroundings could be beautiful might seem anathema. To the outside world, the name “Dachau” is synonymous with the Nazi system of terror that emerged from the concentration camp established on the outskirts of the town in March 1933. More than 200,000 prisoners passed through the camp, including Communists, Socialists, trade unionists, Jews, Sinti and Roma, homosexuals, religious leaders, criminals, and so-called “asocials” (a catch-all prisoner category used to justify the incarceration of diverse groups of people deemed unfit for the “national community”). Approximately 40,000 prisoners were executed, starved, worked to death, or succumbed to disease in the camp between 1933 and 1945. The Dachau concentration camp served as a model for all other camps and as a training site for the SS-men who guarded them.

The camp was located approximately twenty kilometers northwest of Munich in a pastoral Upper Bavarian landscape that resembles a life-sized Caspar David Friedrich painting. The Amper River meanders through the city of Dachau, and atop the hill in the center of town is the palace which served as the former summer residence of the Wittelsbach dynasty that ruled Bavaria until 1918. The palace gardens afford visitors a wonderful panorama of the Munich skyline with the Alps discernible in the background on a clear day.

[Image description: A paved road lined by a barbed-wire-topped wall with watchtowers of the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site on the left-hand side and trees on the right-hand side.]

And so it was that I found myself on a lovely autumn afternoon bicycling through Dachau’s countryside with a specific destination in mind. Two kilometers north of the concentration camp memorial site lies another memorial for the SS-Schießplatz Hebertshausen, the former practice shooting range for the SS-men who trained in Dachau. It was here that SS officers executed more than 4,000 Soviet POWs between 1941 and 1942. These Soviet POWs were transported from the concentration camp, often immediately upon their arrival in Dachau, to the shooting range where they were forced to stand in rows of five as they awaited their deaths.[1]

[Image description: A grassy and tree-lined landscape with a dirt road in the center leading back to the memorial site of the former SS-Shooting Range Hebertshausen.]

Perhaps it is because I knew this history before I visited the site that I found the juxtaposition between these events and the place itself especially jarring. The skies that day were a brilliant blue, and the site was nestled between agricultural fields ready for the autumn harvest. At the entrance to the poplar-lined road leading back to the former shooting range, local farmers had set out pumpkins and gourds for sale on the honor system. Groves of trees concealed the memorial site from the main road. It seemed impossible to reconcile these peaceful scenes with the extraordinary crimes perpetrated there.

[Image description: Three photos of pumpkins and gourds for sale at the entrance to the memorial site of the former SS-Shooting Range Hebertshausen with poplar trees and agricultural fields in the background.]

It was only years later, after discovering Andrew Charlesworth’s article “The Topography of Genocide,” that I was able to articulate better why my visit to Hebertshausen had been so disconcerting. Charlesworth writes that we often expect Holocaust-related sites to exude a sense of doom and gloom commensurate to the crimes they witnessed, when in fact, “the genocidal actions at the heart of Nazi racial policy occurred in ordinary landscapes and were fashioned out of the everyday materials found in those locations.”[2] The ordinariness of these landscapes confronts us with our own proximity to the events, much like color photographs erase the temporal distance conveyed by images in black-and-white. The crimes of Nazi Germany were not confined to barbed-wired camps but rather transpired in the broad daylight of innumerable places and landscapes.

Over the past fifteen years, historians and geographers have begun investigating the roles of space and place in the Holocaust.[3] They have examined the mental and physical spaces associated with it—both the geographical concepts that informed Nazi policymaking as well as the many physical sites (camps, ghettos, execution sites, hiding places, and localities) inseparable from our understanding of the Holocaust.[4] Recent work that more explicitly weds environmental history and the Holocaust is charting out even further territory for academic exploration.[5] Accompanied by a turn to microhistories of the Holocaust, this focus on place-specific features “humanizes abstract ideas” by obliging us to grapple with the dynamics of genocide on a local scale.[6] This “shock” that results from “the specificity of place” concretizes abstract phenomena and divulges the ordinariness of everyday places of mass murder.[7] Far from being exceptional, the SS-shooting range at Hebertshausen was one of countless such sites throughout urban and rural Europe.

Beyond this shock factor, however, an assessment of topography has revealed how perpetrators and victims alike interacted with or exploited natural landscapes during the Holocaust. Sand dunes, forests, and rivers across Europe served as convenient killing sites as well as places to discard bodies and conceal crimes.[8] At the same time, dense forests in central Europe provided refuge for several thousand Jewish refugees and partisans.[9] Place mattered in the Holocaust, for finding oneself “here rather than there” often determined one’s chances of survival.[10] In the Netherlands, for example, the country’s flat topography offered few natural hiding alcoves and has been suggested as a contributing factor for the high death rate of Dutch Jews.[11] By reading landscapes, historians can elucidate how victims experienced the Holocaust as both “a physical reality” as well as “a cognitive process.”[12]

More than illuminating experiences, however, attention to landscapes can also underscore the agency of victims in the face of persecution. An accommodating landscape alone was not enough to guarantee survival. One also needed to know intimately the local environment to utilize it to their advantage. The story of Jakob Mogilnik, as recounted in his testimony given to the USC Shoah Foundation in 1996, reveals how extensive knowledge of the local topography was critical for one’s survival in hiding.

Jakob Mogilnik was born the youngest of six children on March 25, 1925 in Widze, a small town that lies today in the Vitebsk Region of Belarus, close to the border with Latvia and Lithuania. It is one of many localities in the heart of what Timothy Snyder has deemed the Bloodlands, a region in central Europe subject to the whiplash of war, conquest, and border changes in the modern era.[13] At the time of Jakob’s birth, Widze belonged to the state of Vilna in Poland, and 1,100 Jews comprised roughly fifty percent of the town’s population.

The Mogilnik family owned a brick factory, a felt factory, and a flour mill in town, and Jakob enjoyed working as a cashier at the mill after school. He spent much of his childhood at the nearby lake where he swam in the summer and went ice-skating in the winter. As a child and a young man, Jakob cultivated intimate knowledge about the topography of Widze and its environs. This type of local knowledge, what James Scott has called mētis—“a wide array of practical skills and acquired intelligence in responding to a constantly changing natural and human environment” proved indispensable in Jakob’s survival during the Holocaust.[14]

In September 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union invaded and divided up Poland. Widze fell under Soviet control, and the Mogilnik family factories and mill were nationalized. In June 1941, Germany attacked the Soviet Union, and German troops occupied Widze. In the wake of the German advance, local Poles and Lithuanians staged pogroms against Widze’s Jewish population—terrorizing local Jews, looting their homes, and eventually killing ninety-four inhabitants. During the pogroms, the Mogilnik family fled to the fields of a nearby village where they remained in hiding for one week before returning to Widze. This was the first time that nature shielded Jakob and his family, but it would not be the last. Over the next four years, Jakob used his knowledge of Widze’s local surroundings to protect himself and his family members.

In November 1941, the Mogilniks moved along with their Jewish neighbors into the newly established ghetto in Widze. Jakob was drafted into a work detail of 160 young Jewish men in June 1942. They marched for several days, west from Widze to the village of Twerecz (today: Tverečius) and on to Mielagėnai, Święciany (today: Švenčionys), Podbrodzie (today: Pabradė), Nemenčinė, over the Wilia River (today: Neris River), and finally turned into a forest. The Jewish populations in most of the towns through which they passed had already been murdered. Once they were in the forest, the men were put to work felling timber. Jakob quickly understood that if the men were not killed immediately, they would soon starve to death for lack of provisions. So he and a friend hatched a plan and escaped, traversing back across the Wilia River, through the forest, and home to Widze.

[Image description: A map from Google Maps plotting a 114-km walking route from the town of Vidzy to Nemenčinė.]

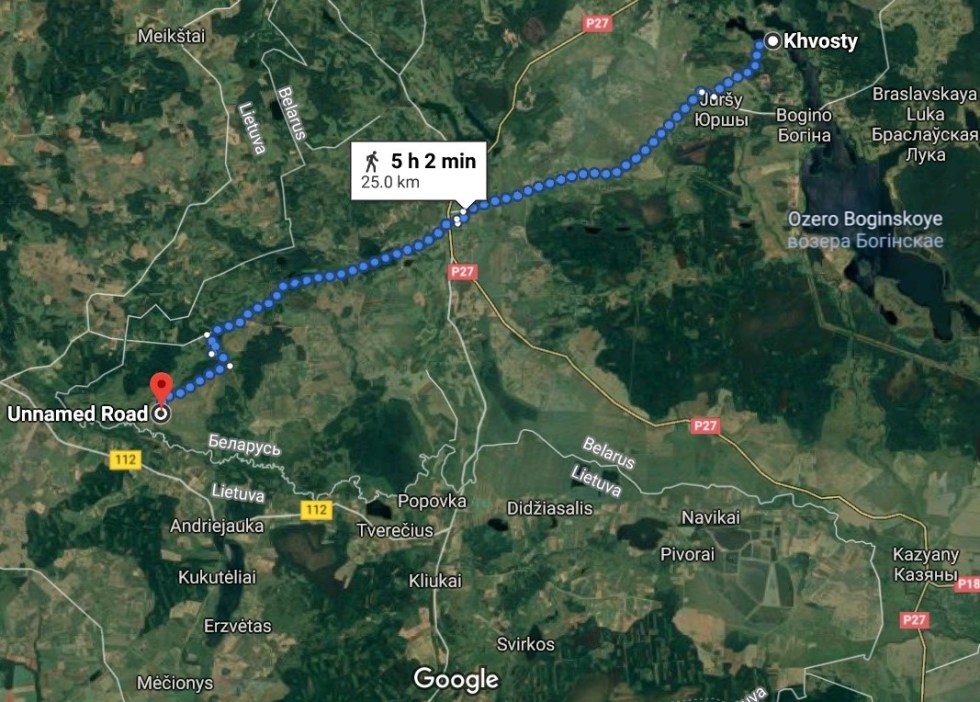

During the next several months, Jakob was transported weekly for forced labor to the village of Khvosty, located thirteen kilometers east of Widze. During these trips, he expanded his networks with local farmers who sometimes gave the Jewish men food. Jakob managed to convince several farmers to dig bunkers in their barns to hide him and his family and friends. But the farmers became nervous when German troops killed local partisans and burned down villages and soon forced them out.

When the Jewish inhabitants of the Widze ghetto were transported to the Święciany ghetto in late summer 1942, Jakob’s father implored his family to accompany them. But Jakob protested, saying: “Look, if we all go to Święciany, something happens, nobody will be alive. I don’t know the territory [in] Święciany.” Jakob knew that their chances of survival were better in Widze where he was more familiar with the area, and he convinced his family to go into hiding. Over the next few months, Jakob worked a territory with a radius of 25-30 kilometers between Khvosty and Mileniszki, often posing as a partisan to collect food. They moved from farm to farm seeking shelter, but intensifying searches and pressure placed on locals by the German occupying forces meant that the Mogilniks ran out of places to hide by autumn 1943.

[Image description: A map from Google Maps plotting a 25-km walking route from the village of Khvosty to an unnamed road near the present-day border between Belarus and Lithuania.]

They hid for several months in a bunker they had dug out near a swamp. A nearby river provided them with access to fresh water, and they collected berries and mushrooms to eat. The onset of winter forced them out of the swamp bunker in pursuit of warmer quarters. They hid in the forest during the day and were soon invited into the home of Paweł and Józefa Wojczys, acquaintances of theirs, to warm up and receive something to eat in the evening. When the Mogilniks asked to dig a bunker there and hide out until spring, Paweł hesitated because he feared for their children. Eventually, however, Józefa convinced her husband to allow them to build a bunker and remain in hiding through the winter.

[Image description: Paweł and Józefa Wojczys, seated on a chair next to each other, with their four children standing behind them. Józefa holds a bouquet of flowers on her lap.]

In the spring, Paweł again became nervous and requested that Mogilniks depart. Jakob asked the farmer to take a letter from them to the local priest: “We knew that the priest is going to tell him to hold us. And maybe he’ll send us something to eat, maybe he’ll give him some money. There was a new priest in town, but he was very friendly to Jews.” After visiting the priest in Widze, Jakob recounts that Paweł returned with 5,000 Marks, two sacks of flour, and a letter from the priest who had told Paweł to allow the Mogilniks to stay because the war would soon be over. According to Jakob, Paweł had determined: “Either we’re all going to die. Or we’re all going to survive.”[15] The Mogilniks remained with the Wojczys family until August 1944 when they were liberated by the Red Army. Jakob, his father David, and his sisters Gitta and Sarah had survived the war in hiding. Paweł and Józefa Wojczys were recognized by Yad Vashem as “Righteous Among the Nations” in 2002.

[Image description: A photo of six people, including Holocaust survivor Jakob Mogilnik with five family members. His niece stands in the middle on a chair.]

Jakob Mogilnik’s story shows that proximity to one’s home, and intimate knowledge of the local terrain, potential hiding places, and places to secure food from nature or friendly neighbors were critical elements of survival. Jakob’s extensive knowledge of Widze and its surroundings helped him and several of his family members evade German authorities.

At times, the genocide of European Jewry seems impossible to understand, its enormity veiled by the very words and figures we employ to describe it. The term “Holocaust” suggests a coherence that belies the intrinsic chaos of its infinite constituent histories. Speaking of the collective “six million” allows us to circumvent the mental anguish involved in trying to account for the approximately 6,000,000 unique Jewish individuals who were murdered. Like the disciplines of history, psychology, and sociology, so too has geography proven that it has much to offer in the quest to move the Holocaust from the realm of the abstract to the tangible. Studying and visiting the many sites associated with the Holocaust and retracing the steps of individual victims serves to powerfully remind us that the Holocaust did not take place on a “different planet” but rather transpired in innumerable ordinary places, most of which still exist in some form today.[16]

[1] Kerstin Schwenke, Dachauer Gedenkorte zwischen Vergessen und Erinnern: Die Massengräber am Leitenberg und der ehemalige SS-Schießplatz bei Hebertshausen nach 1945 (Munich: Herbert Utz Verlag, 2012), 86-87.

[2] Andrew Charlesworth, “The Topography of Genocide,” in The Historiography of the Holocaust, ed. Dan Stone (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 216.

[3] See e.g. Tim Cole, Holocaust City: The Making of a Jewish Ghetto (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 2003); Anne Kelley Knowles, Tim Cole, and Alberto Giordano, ed. Geographies of the Holocaust (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2014); Paolo Giaccaria and Claudio Minca, ed., Hitler’s Geographies: The Spatialities of the Third Reich (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2016); Tim Cole, Holocaust Landscapes (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

[4] Dan Stone, “Holocaust Spaces,” in Hitler’s Geographies, 46.

[5] Tim Cole, “‘Nature Was Helping Us’: Forest, Trees, and Environmental Histories of the Holocaust,” Environmental History 19, no. 4 (October 2014): 665-686; Timothy Snyder, Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning (New York, NY: Tim Duggan Books, 2015). See also the recent contributions in the special issue on “The Environmental History of the Holocaust,” Journal of Genocide Research 22, no. 2 (2020).

[6] Claire Zalc and Tal Bruttmann, “Introduction: Toward a Microhistory of the Holocaust,” in idem., Microhistories of the Holocaust (New York, NY and Oxford: Berghahn, 2017), 6.

[7] Stone, “Holocaust Spaces,” in Hitler’s Geographies, 53.

[8] Charlesworth, “Topography,” 218-224; Cole, Holocaust Landscapes.

[9] Suzanne Weiner Weber, “The Forest as a Liminal Space: A Transformation of Culture and Norms during the Holocaust,” Holocaust Studies 14, no. 1 (2008): 35-60; Cole, “‘Nature Was Helping Us.’”

[10] Cole, Holocaust Landscapes, 6.

[11] Suzanne D. Rutland, “A Reassessment of the Dutch Record,” in Remembering for the Future: The Holocaust in an Age of Genocide, Vol. I: History, ed. John K. Roth and Elisabeth Maxwell (Basingstoke and New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 534.

[12] Stone, “Holocaust Spaces,” 49-50.

[13] Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2010).

[14] James Scott, Seeing Like a State How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), 313.

[15] For Jakob Mogilnik’s full testimony, see Jakob Mogilnik, Interview 20789, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation, 1996.

[16] In his testimony during Adolf Eichmann’s trial in 1961, Yehiel Dinur famously referred to Auschwitz-Birkenau as “Planet Auschwitz.” For more information on Eichmann’s trial and the impact of Dinur’s comment, see Hanna Yablonka and Moshe Tlamim’s “The Development of Holocaust Consciousness in Israel: The Nuremberg, Kapos, Kastner, and Eichmann Trials,” Israel Studies 8, no. 3 (2003): 1-24.

*Cover image credit: Photo by author.

[Cover image description: Trees and foliage surrounding a dirt road leading back to the memorial site of the former SS-Shooting Range Hebertshausen.]